A Family Passion

A PASSION

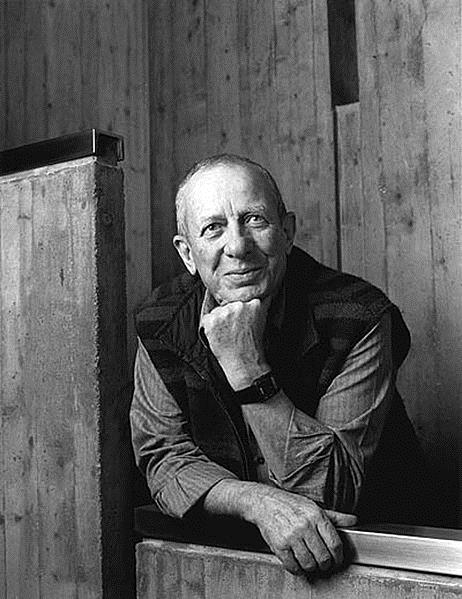

Why do people become so gripped by the passion to make wine? I asked this question together with Luigi Veronelli, the most important wine philosopher-writer in Italy when, many years ago, my then associate Edmond de Rothschild invited us to Château Clarke to spend a long weekend with Emile Peynaud, the greatest oenologist in France and beyond as well as professor at the University of Bordeaux. Edmond was the largest single shareholder of Château Lafite, but his cousins – with whom I later founded Rocca di Frassinello in the Maremma – were not inclined to involve him in its management. For this reason he decided to buy Château Clarke, with the ambition of making it the Lafite of the 21st Century. Edmond didn’t succeed, because he left this world before he could bring his project to fruition. But that weekend he gave Veronelli and myself the answer to the question that we’d asked ourselves, he as narrator and I as a journalist already bitten by a passion for winemaking. Wine becomes a passion, according to Edmond (and I agree), because it is a permanent challenge, almost like being the official challenger for the America’s Cup every year, all year round.

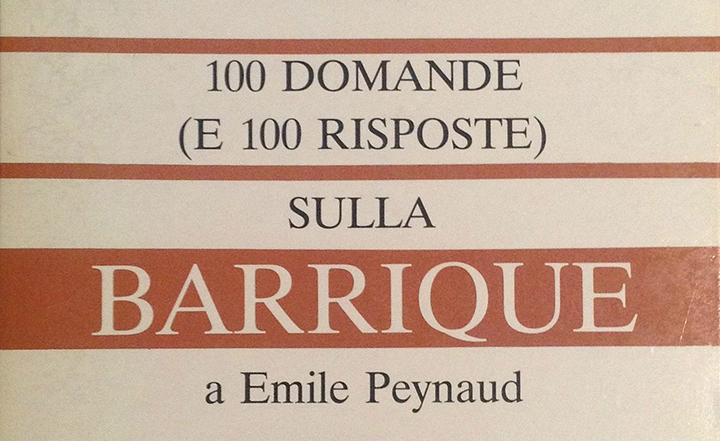

Because making wine, like competing in the America’s Cup, forces you to consider every fundamental detail, to search frantically for the best solutions when you come up against the vagaries of the weather, and even if the crew on-board or in the winery are perfect you never know how things will turn out; you think you know the race course or your vineyards perfectly, but there is always the unexpected – the changing wind, the soil of the vineyard which, with huge variations even within the space of a hectare, can give different results from one year to the next. You do everything to achieve the best possible outcome, but there is always the unexpected to excite and surprise you. It’s like this because the vineyard is life, it lives and often reacts like a person if you don’t know how to caress it, to treat it as the one you love most on earth. Not to mention the moment when the wine is finally in the cellar and the energy taken from the vine’s roots continues to live; first in the vinification vats and then in the barriques, or “carati”, as Veronelli correctly called them in Italian. Luigi always remembered the Italian proverb that said “good wine comes in small barrels”, coined well before the fortuitous discovery of the qualities of barriques, which in the 1800s were used on sailing ships to transport wine from Bordeaux to England. As Professor Peynaud explained to us in a long interview – later a book called 100 questions and 100 answers about barriques (which we published under the Castellare-Fattoria name and was very important in enabling Italian wines to equal and then overtake the quality of the French) – their small size (225 litres) allowed a larger quantity of wine to come into contact with the wood, and the thin slats, narrower than those in large barrels, enabled oxygen to pass through and transfer to the wine the noble tannins of oaks from the Massif Central.

And precisely for this reason we joined Edmond, in-love with Italy and its wines like few others, in founding the Compagnie Vinicole Conseille for the exchange of technology between Italy and France.

Challenge (and therefore passion) is the engine of all activities, but in making wine and in sailing there is always the added excitement of the unexpected. A passion for sailing and for making wine has gone together in our family for many decades. The same was true of Edmond, who was as fond of his Gitana, which he used to race in the maxi yacht category, as he was of Lafite and Clarke. That may be why we were such great friends. And it was certainly that first connection with the most famous banking family in the world that later, after developing Castellare di Castellina in the Chianti Classico region, enabled us – together with Eric de Rothschild, cousin of Edmond and president of Domaines Barons De Rothschild-Lafite – to found our family’s second estate, Rocca di Frassinello, in the Tuscan Maremma a few kilometres from Bolgheri.

A FRIENDSHIP

The starting point for my friendship with Eric and his highly-talented CEO Christophe Salin was the stock market listing of Class Editori, the publishing house that I founded in 1986. Eric and his cousin David had successfully relaunched the Banque Rothschild in Paris after its nationalization, ordered by French President François Mitterrand during his first term when he was supported by the French Communist Party. The Milan branch of the new Banque Rothschild acted as advisor for the listing, giving us the opportunity to meet Eric. While he was on a short stay at Bolgheri we found ourselves having lunch at Gambero Rosso, a restaurant created by one of the world’s most brilliant chefs, Fulvio Pierangelini.

During lunch (Fulvio opened at 1 p.m. just for us) I told Eric that since there were no longer any terrains suitable for wine growing left in the Chianti I had bought 50 hectares in the hinterland of Castiglione della Pescaia and Punta Ala. “Let’s go and see them”, replied Eric, with the curiosity that has always driven him. Once we were there, appreciating the position and the terrain devoid of vineyards he said to me: “If you manage buy the various estates of the valley, 500 hectares, then let’s do a joint venture because, Paulò, le vin est un affair fonciér pour nostres nephews”, in a spontaneous mix of French and English. Over and beyond being a matter of passion, Eric’s idea was and is that wine can bring about an increase in land values so that it is advisable, before planting the vineyards, to buy a lot of land.

A PROJECT

Rocca di Frassinello, designed by Renzo Piano, was inaugurated 21 June, 2007 – the summer solstice. In creating this, the first joint venture in wine between Italy and France, the passion that drove us was not the desire to create a monument to customers or to wine. As Renzo Piano says, a winery is first and foremost a production plant, even if it transforms the products of nature rather than manufacturing cars. In full agreement with Renzo, a close friend since well before his first great achievement of designing the Beaubourg in Paris, we put great passion into creating a workshop, as efficient and rational as possible, without marble or luxuries, with exposed concrete walls and a completely innovative layout. A large square design centred on the most important phase in the ennobling of wine: the barrel room, large enough for 2,000 barriques; around it, like a large frame, two sides at one level only for the vats and two sides at two levels for the other functions.

Everything is arranged so as to never require the use of pumps: the grapes arrive in a large square, which Renzo baptised the “sagrato” (churchyard), are selected and end up in the fermentation vats by force of gravity through small windows in the floor. Renzo had also already tasted the passion for making wine at his family’s winery in Ovada, Piedmont, and he often chides me about the fact that he devoted much more time to Rocca di Frassinello, his only winery, than to creating the new headquarters of the New York Times. And Renzo too loves sailing as much as architecture.

The nearly 100 hectares of vineyards, being conceived as an Italian-French joint venture, are planted with equally divided grape varieties: 50% Italian and 50% French, while all wines are blends, excluding the Baffonero which, in the spirit of the America’s Cup, serves as a challenger to Masseto, (100% Merlot), the most famous Italian wine produced by our friends, the Marchesi Frescobaldi family, owners of the Ornellaia estate. Exactly the opposite of the philosophy of Castellare di Castellina.

The legacy of the days spent at Château Clarke with Peynaud was extraordinary, and led me to take three decisions regarding Castellare:

1) that I would go all out for Sangiovese, which in the Chianti we call Sangioveto, since in Peynaud’s opinion it was a vine of extraordinary untapped potential

2) that I would plant the first experimental vineyard in the Chianti, with 30 different clones of Sangioveto to fill a void left by the oenological authorities (which took place in collaboration with Professor Attilio Scienza of the University of Milan)

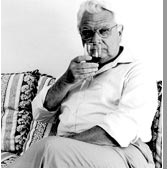

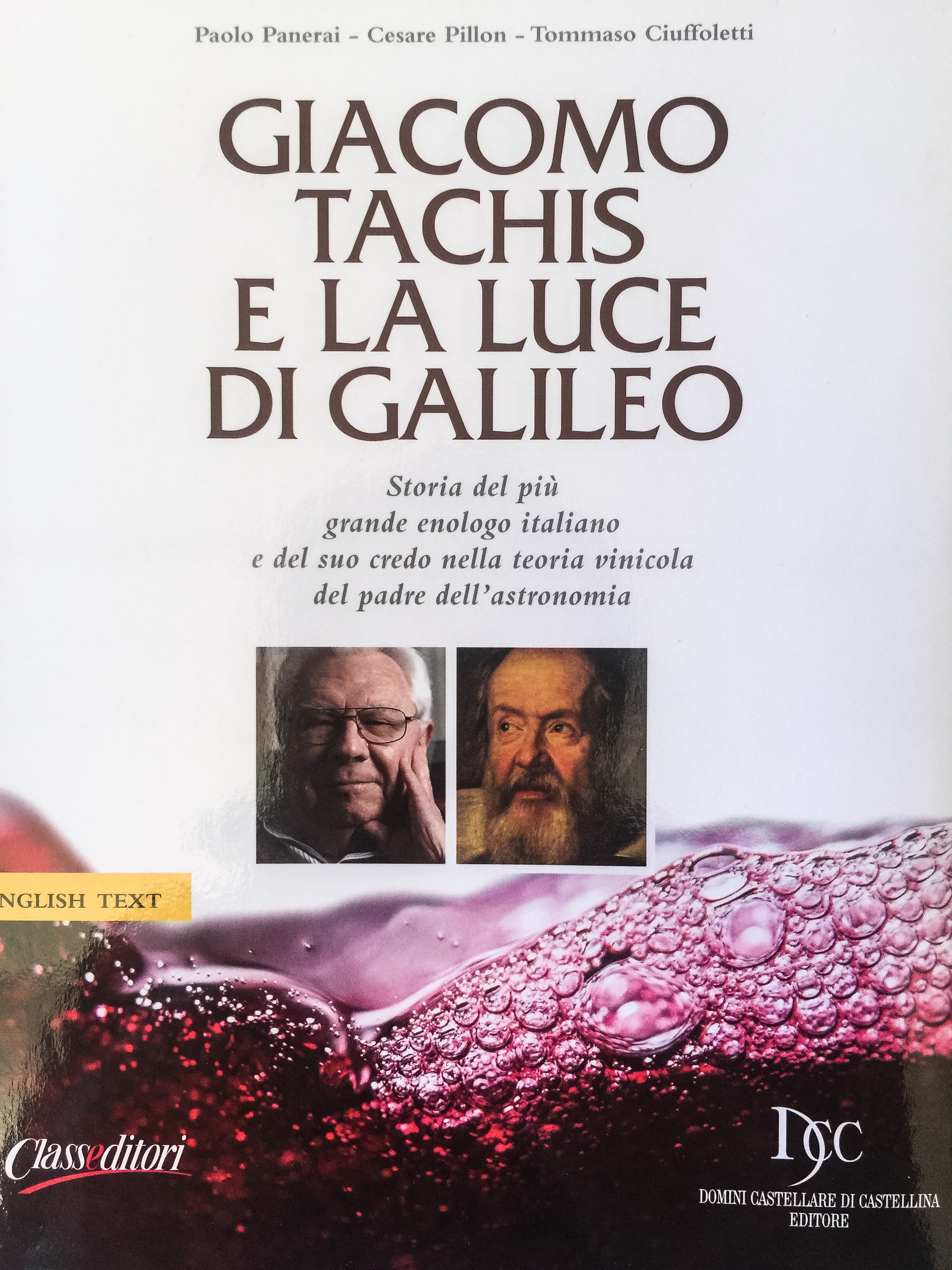

3) that the greatest, most important wine that we would make at Castellare would be made from Sangioveto and another indigenous vine, Malvasia Nera, completely contradicting the approach of the greatest Italian winemaker, Giacomo Tachis, who for Tignanello had decided to unite Sangiovese with the two main French varieties.

Tachis’s friendship and respect for Alessandro, who the creator of Tignanello, Sassicaia, Solaia and Turriga chose as his ideal successor, led to our passion for the other two Domini Castellare di Castellina estates, Feudi del Pisciotto and Gurra di Mare. Both of which are in Sicily. Feudi is located in the only Sicilian DOCG area at Cerasuolo di Vittoria, while the vineyards of Gurra di Mare extend right up to the beach at Menfi, the homeland of Planeta. It was a violent passion because Tachis, a native of Piedmont who became famous for Tuscan wines, was the architect behind the rebirth of Sicilian wine as Regional Institute of Vines and Wine consultant. This is probably the most praiseworthy initiative to have been taken on what is the most remarkable island in the Mediterranean, but also the most devastated by inefficiencies. Tachis explained to Alessandro and myself that, as Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo Galilei and also Dante also believed, Wine is Light and Mood. And nowhere else in the world are the light (the sun) and the moods of the land so extraordinary as in Sicily: it is no coincidence that thousands of years ago it was called Enotria, which by transposition gave the word “enos” the meaning of wine (thus oenology). To increase our passion for winemaking, Tachis threw us an even more exciting challenge: he suggested that we produce grape varieties in Sicily that no one would think capable of producing great wines in the Sicilian heat. And so we planted Semillon and Gewürztraminer to make passito, and Pinot Noir to make the best wine of Feudi. Pinot Noir in particular is an extraordinary challenge, because it is the dream of every producer to vinify the noblest of grapes. Others had also attempted this in Sicily, but only the secrets given to us by Tachis along with Alessandro’s passion, expertise and specialisation in the most difficult grape variety on earth, enabled us to reap not the heat, but the light and moods of the lands of Sicily. Our Pinot Noir is called L’Eterno, and the label shows the hand of the extraordinary sculpture by Giacomo Serpotta, the greatest sculptor in the history of Sicily. Feudi del Pisciotto funded the restoration of this sculpture with part of the proceeds from sales of wines with labels designed by Italian fashion designers, including Versace, Ferrè, Giambattista Valli, Alberta Ferretti, Missoni and others. All agreed to waive their royalties in order to help the rebirth of Sicily-Enotria. This for us is another passion, as great as and intertwined with our passion for wine, because wine is civilization, history, and – being derived from the Latin word venus – beauty.