Tasting the wine

A good wine is like a treasure, a coffer of magnificent flavours, aromas and sensations that allow the imagination to fly away to wonderful and often distant places. Here, you will find a few tips on how to approach a tasting, intended for those who are not familiar with the secrets of the world of wine, and without the expectation to train new sommeliers, but rather with the intent to continue to inspire and excite those who never get tired of learning about wine. The commitment required on the part of a good taster is that he or she pushes themselves beyond their basic knowledge, beyond the recognition of basic sensations such as sweet, sour, salty, to project themselves towards the discovery of less familiar aromas and flavours capable of enriching the sensory analysis. Wine tasting starts with a visual analysis, particularly important in terms of all the information that can be obtained in relation to the health, conservation, evolution and structure of the wine.

After filling a long-stemmed glass to a third of its capacity, the glass is held by the stem to avoid any outside influence of odours and is brought into one’s field of vision, inclined at a 45° angle. It is recommended that tastings are carried out in a neutral room, with white walls and free of any odours or excessive sound sources which could potentially influence the assessment. The main characteristics on which to focus are presented below:

- limpidity, namely the absence of suspended particles, tinting and turbidity;

- colour tonality: in white wines it ranges from greenish yellow to straw, gold and amber yellow; in reds from purple to ruby, garnet and orangey red;

- hues, a source of information on the age and level of development of the wine, can be noted in the edges / rim of the liquid;

- liveliness, referring to the brightness of the colour: dull, dark, light, lively, bright.

Observing the wine while it is poured and slowly swirling the glass, it is possible to understand its consistency: the more it flows, the weaker the structure and degree of alcohol, the more dense it is, the stronger its structure will be, and presumably the degree of alcohol and the glycerine content, element that adds complexity and softness to the wine and which can be noted on the inside of the glass after its contents have been swirled around: good wines leave rings and transparent legs of glycerine. For sparkling wines the effervescence of the product must also be evaluated, characteristic due to carbon dioxide that is released when the wine is poured, paying attention to the intensity, texture and persistence of the perlage.

The second phase of the tasting consists in the olfactory analysis. Every odour-related perception is attributable to the interaction between the volatile molecules present in wine with the receptors in the olfactory mucosa. The complexity of this phase of tasting lies in the ease of perceiving an odour but the extreme difficulty in identifying it: everything is based on the experience of the taster and in their having studied and classified specific odours in the past. The wine is now examined based on:

- overall intensity: the intensity of the odour perceived, both while the wine is standing still in the glass, as well as after the wine is swirled, causing it to release volatile molecules;

- complexity: breadth and number of positive odorous expressions;

- finesse: elegance and clarity of the odours;

- presence and intensity of individual descriptors: identification by analogy of specific odorous perceptions (fruity, floral, spicy, etc.)

The third tasting phase consists in the taste-olfactory analysis during which the consistency of visual and olfactory sensations with respect to those of a taste-olfactory nature are assessed.

First the softness of the wine is assessed:

- sugar: the wine can be dry, medium dry, medium sweet, sweet or excessively sweet;

- alcohols: the wine can be light, light warm, medium warm, warm or alcoholic;

- softness: the wine can be sharp, scarcely soft, quite soft, soft or velvety.

Next, the analysis continues with the hardness of the wine served:

- acids: the acidity of a wine gives a pleasant sensation of freshness of taste. The wine can be flat, scarcely fresh, quite fresh, fresh or acidulous;

- tannins: astringency is a tactile sensation due to the presence of tannins. The wine can be: flabby, scarcely tannic, quite tannic, tannic or astringent;

- minerals: the wine can be tasteless, scarcely tasty, quite tasty, tasty or salty.

The analysis then proceeds with the evaluation of:

- the wine’s structure, term referring to the depth or body of the wine determined by all of the substances that make up the extract: polyphenols, fixed acids, salts, sugars and glycerine;

- the balance between softness and hardness of the wine: a wine is balanced when these two aspects complement each other, without one prevailing over the other;

- the intensity of the taste-olfactory perceptions;

- the persistence measured in terms of the duration of the wine’s taste-olfactory sensations;

- the quality of the taste-olfactory perceptions.

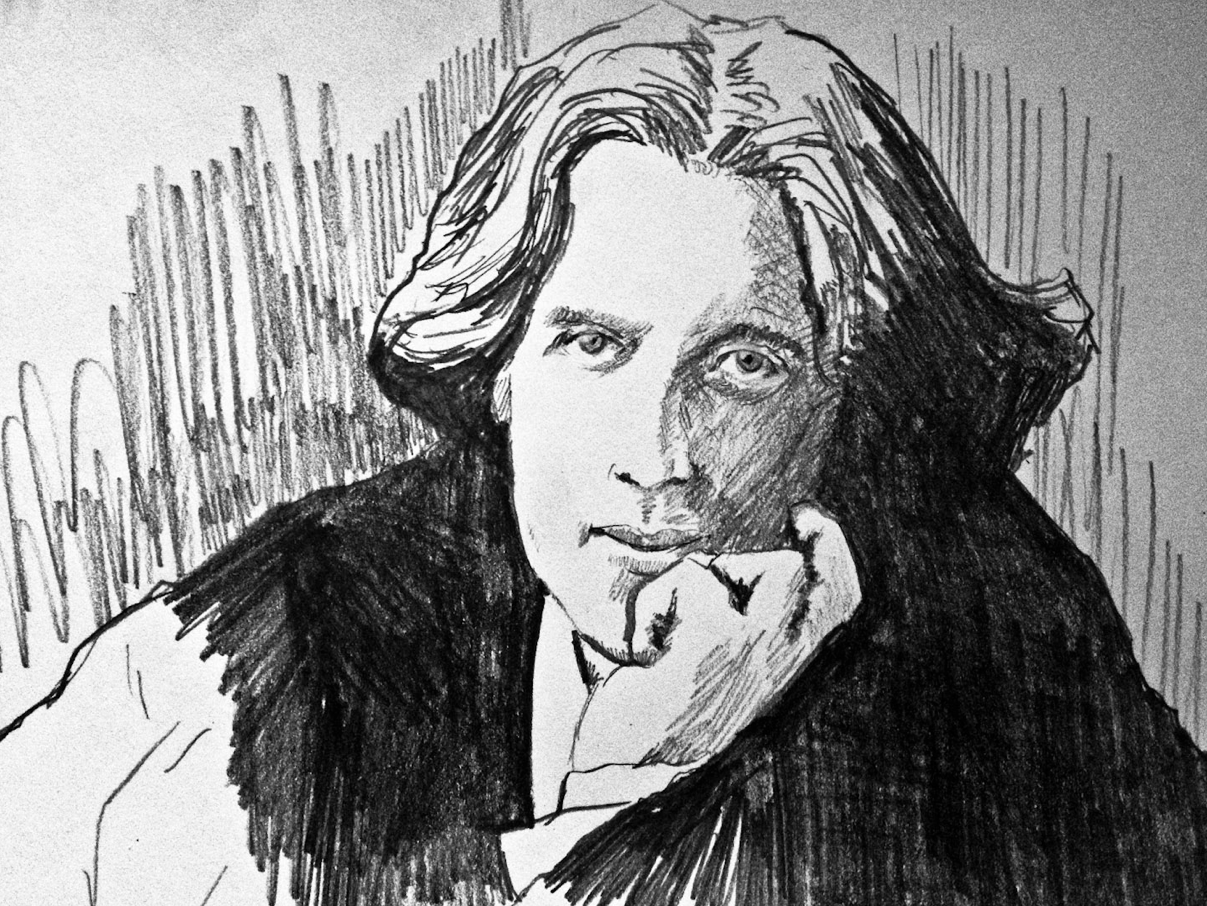

The guidelines outlined above aim to encourage a more informed and professional tasting experience, with the recommendation that, in the words of Oscar Wilde “to know the vintage and quality of a wine one need not drink the whole cask”.